Enhancing Spatial Experience Through Peripheral Vision in Cognitive Architecture

Introduction

In architectural design, we often focus on what we see directly in front of us. However, much of our spatial experience is shaped by peripheral vision—our ability to sense the environment beyond our focused gaze. While central vision allows us to perceive fine details, peripheral vision is responsible for detecting movement, depth, and spatial context, making it a fundamental aspect of how we experience and navigate built spaces.

Peripheral vision plays a crucial role in creating an intuitive and immersive experience of space. It provides us with a subconscious understanding of our surroundings, influencing our sense of safety, comfort, and engagement. Cognitive architecture leverages this by designing environments that subtly guide movement, enhance awareness, and evoke emotional responses. By thoughtfully incorporating elements that engage peripheral vision—such as layered depth, tactile cues, dynamic lighting, and biophilic elements—architects can transform static spaces into fluid, immersive experiences that feel natural and intuitive.

This article explores how cognitive architecture can harness the power of peripheral vision to create environments that are not only functional but also deeply resonant and human-centric.

1. The Power of Peripheral Vision in Spatial Awareness

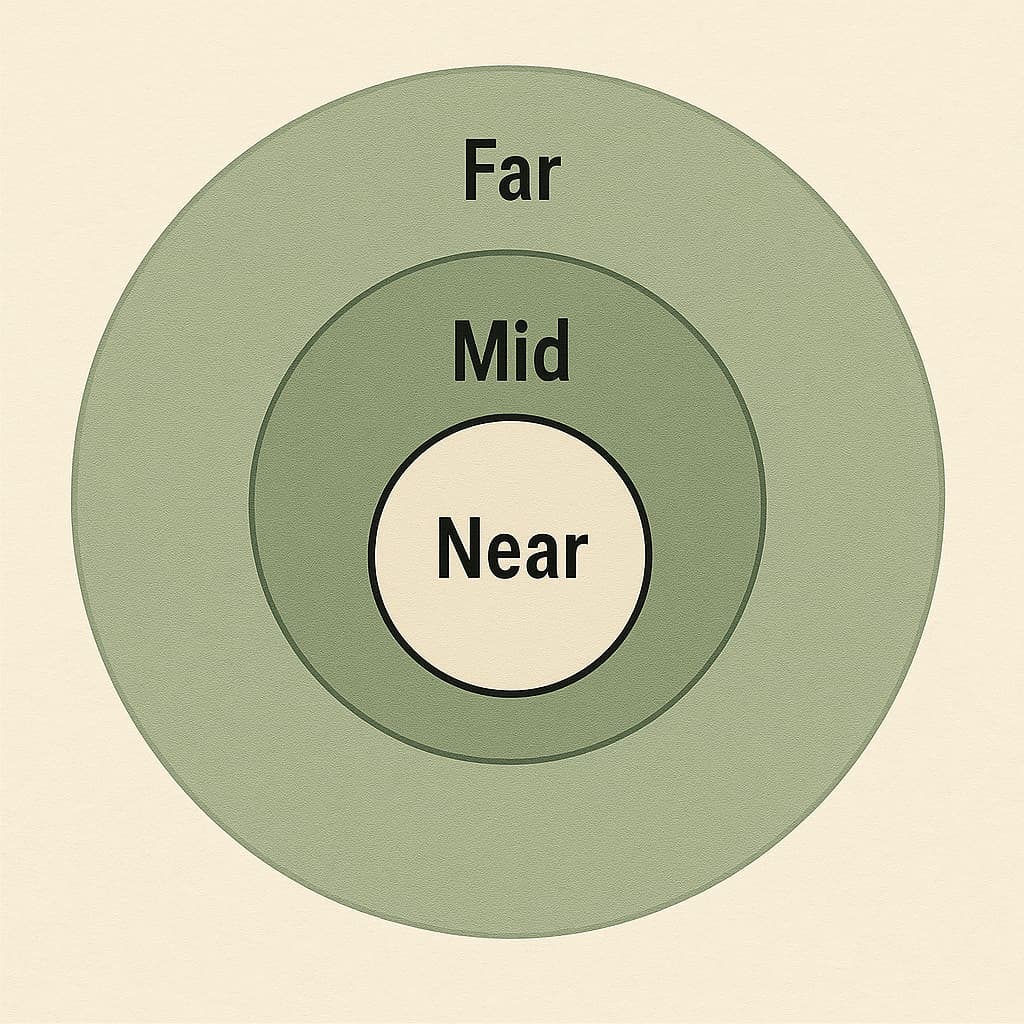

Peripheral vision refers to the part of our visual field that extends beyond the central focus of our eyes, allowing us to perceive motion, depth, and changes in contrast without directly looking at them. It is divided into three main zones:

- Near Peripheral Vision (5-30 degrees from the center of focus) – Helps with orientation and detecting nearby objects.

- Mid Peripheral Vision (30-60 degrees) – Sensitive to movement and spatial transitions, contributing to subconscious wayfinding.

- Far Peripheral Vision (beyond 60 degrees) – Detects motion at the edges of awareness, playing a key role in alertness and environmental immersion.

Unlike central vision, which is responsible for recognizing fine details and reading text, peripheral vision is more attuned to:

- Detecting movement – Helping us sense approaching objects or changes in our surroundings.

- Registering contrast and light variations – Contributing to spatial awareness.

- Providing depth perception and continuity – Integrating fragmented visuals into a holistic perception of space.

Research in neuroscience and psychology suggests that peripheral vision significantly impacts how we experience and interpret spatial environments. It creates a sense of spatial enclosure or openness, helps us anticipate movement, and enhances the overall cognitive mapping of a space. When designed effectively, environments that engage peripheral vision can improve wayfinding, increase comfort, and reduce cognitive strain, making them ideal for public spaces, workplaces, hospitality environments, and healthcare facilities.

Cognitive architecture utilizes these properties to create environments that feel expansive, dynamic, and seamlessly connected, improving navigation and emotional engagement.

2. Designing for Peripheral Vision: Layered and Tactile Cues

Layering elements in architecture helps peripheral vision construct depth and movement, reinforcing a space’s fluidity. Effective strategies include:

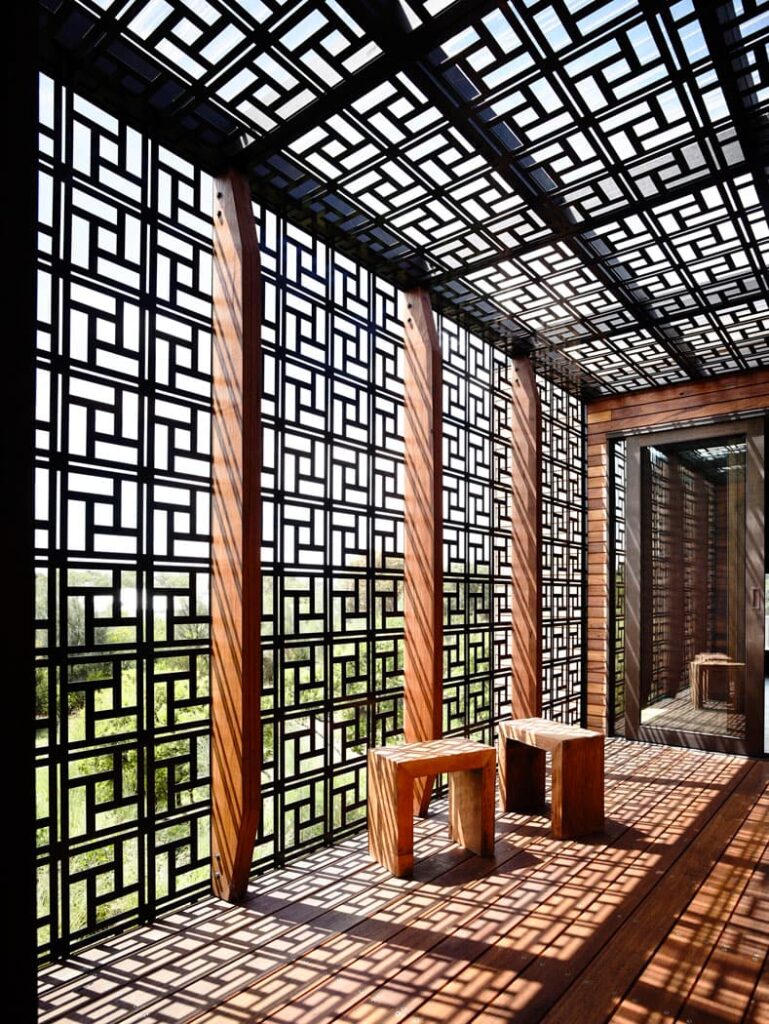

- Using transparent or semi-permeable partitions (e.g., glass screens, lattices, or slatted walls) to create multiple planes of visual perception.

- Designing gradual transitions in lighting, textures, and materials to guide movement and differentiate spatial zones.

- Incorporating curved pathways and open sightlines, which support subconscious navigation and eliminate abrupt spatial separations.

By implementing these techniques, spaces become more legible and immersive, allowing people to navigate them effortlessly.

Tactile Richness and Textural Engagement

Since peripheral vision is closely connected to other senses—particularly touch—tactile elements reinforce spatial perception. This can be achieved through:

- Contrasting materials (wood, stone, fabric, metal) that create subtle sensory variations.

- Wall reliefs and patterned surfaces, which register in peripheral awareness, adding layers of depth.

- Floor material transitions, such as shifting from polished stone to textured wood, which signal spatial shifts without requiring direct focus.

When thoughtfully integrated, these elements make a space more engaging, guiding occupants through a multisensory journey.

3. Lighting, Shadows, and Dynamic Movement

Light and shadow play a crucial role in how we perceive space. Peripheral vision is highly sensitive to contrast, gradients, and movement, making dynamic lighting an essential design tool. Effective strategies include:

- Using indirect lighting along walls and pathways to create a soft, intuitive guide for movement.

- Integrating natural light variations, such as dappled sunlight filtering through perforated facades or foliage, which creates a dynamic and ever-changing atmosphere.

- Incorporating shadow play and reflections, which add layers of depth, making spaces feel more expansive.

- Adding kinetic elements, such as water features or hanging installations, which subtly activate peripheral awareness through movement.

By leveraging these techniques, architects can craft spaces that feel alive and responsive, enhancing engagement and comfort.

4. Wayfinding and Intuitive Navigation

Peripheral vision naturally assists in navigation, allowing people to move through spaces without actively searching for directional cues. Cognitive architecture enhances this by incorporating:

- Subtle contrasts in flooring materials to define different functional zones.

- Variations in ceiling heights and overhangs, which subconsciously indicate transitions between spaces.

- Guiding light pathways, such as recessed LED strips or natural skylights, which help direct movement without visual overload.

- Biophilic elements, including trees, water features, and natural textures, which intuitively orient occupants through recognizable environmental patterns.

These elements make navigation effortless, reducing cognitive load and enhancing spatial clarity.

5. The Role of Biophilic and Multi-Sensory Design

Biophilic design, which incorporates nature into architecture, engages peripheral vision and multiple senses, creating harmonious, immersive environments. Key elements include:

- Nature-inspired textures and materials, such as wood grains, stone surfaces, and organic patterns, which offer a rich, tactile experience.

- Acoustic layering, where subtle sounds of water or rustling leaves reinforce depth perception and relaxation.

- Dynamic environmental factors, such as shifting air currents, temperature variations, and natural scent integration, which heighten spatial awareness and well-being.

By seamlessly integrating these principles, architects can create spaces that reduce stress, improve cognitive function, and enhance the overall sensory experience.

Conclusion

Peripheral vision is an often-overlooked but powerful tool in architectural design, shaping how people experience and navigate spaces at a subconscious level. By integrating layered depth, tactile cues, dynamic lighting, and biophilic elements, cognitive architecture creates environments that feel intuitive, immersive, and emotionally engaging.

Through thoughtful design, peripheral vision transforms fragmented visuals into a cohesive spatial experience, allowing users to connect with their surroundings effortlessly. By applying these principles, architects can craft built environments that go beyond functionality, creating spaces that are not only visually appealing but also deeply resonant and human-centric.

How can these principles be applied in your next design project?